Privilege review during discovery requires an understanding of what is protected by the various privileges present in a case and a working knowledge of how to efficiently conduct the document review. We find that attorneys frequently do not consider the possible privilege issues in their case until they have started screening documents or until the first pass of document review is completed.

We strongly recommend that attorneys discuss with their clients all the relevant privileges before the time for the document review. Questions to be asked include: Do the documents reveal communications with any attorney, medical professional or clergy? Do the documents contain confidential personal information such as social security numbers, tax information, employee information or trade secrets? Do the documents contain any work product that was created by an attorney or at the direction and control of an attorney? Is there any evidence of communications between spouses? Do the documents contain any HIPPA protected medical records?

There can be many other privileges at issue in a case. However, this is a starting point for discussion with clients.

The key is for the review team to consider all of the possible privilege issues before starting a document review in order to create the privilege log simultaneously with the document review. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (and most corresponding state law) dictate that a privilege log expressly explain why information was withheld for a specific privilege. USCS Fed Rules Civ Proc R 26(b)(5). The privilege log must “describe the nature of the documents, communications, or tangible things not produced or disclosed—and do so in a manner that, without revealing information itself privileged or protected, will enable other parties to assess the claim.” Id.

Carden Rose, Inc. partners with Everlaw for hosting cases for document review. We work with our attorney clients to identify the different privileges in a particular case. As mentioned above, privileges can range from communications that could be protected by the physician-patient privilege under California Evidence Code sections 990-1007, information protected by HIPAA, or personal communications such as the Spousal Privilege pursuant to Evidence Code sections 980-987. After identifying the relevant privileges in a matter, issue coding is created in Everlaw for coding during attorney review. A screenshot from Everlaw is embedded below as an example.

The reviewing attorney can add a “Note” in Everlaw that explains why a document is privileged, such as “Communication from patient to physician regarding medical treatment.” This review methodology allows compliance with the Rule 26(b)(5) requirement to “describe the nature of the documents, communications, or tangible things not produced or disclosed—and do so in a manner that, without revealing information itself privileged or protected, will enable other parties to assess the claim.”

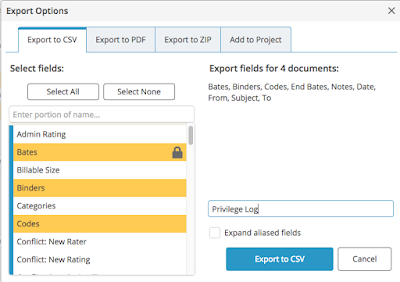

The reviewing attorney can add a “Note” in Everlaw that explains why a document is privileged, such as “Communication from patient to physician regarding medical treatment.” This review methodology allows compliance with the Rule 26(b)(5) requirement to “describe the nature of the documents, communications, or tangible things not produced or disclosed—and do so in a manner that, without revealing information itself privileged or protected, will enable other parties to assess the claim.” A privilege log can be created directly from Everlaw. Once a review is completed the reviewer can export a CSV file or PDF with the fields that are required from the privilege log, such as the claimed privilege under Codes, the note explaining the privilege, and other objective fields, including To, From, Date, Subject, MD5 Hash Value, and whatever else counsel wishes to include.

The exported file will include the user who conducted the review, who made the notes, and the specific information such as the time of creating any coding decisions. This information can be removed for the purposes of the privilege log to avoid creating any confusion. Below is an example of an export with a limited number of fields. More fields can be added as required by the case.

There are multiple ways to conduct a privilege review. This workflow empowers attorneys to maximize the value of their time in document review by identifying potential privileges, adding the appropriate issue codes to expressly claim a privilege, and sufficiently describe the claimed information for the opposing side to assess the claim.